Well, things have been prepared, but the campaign is facing the classic trouble of no one’s times lining up. You’d think it’d be easier with roommates, but I guess not.

The extra time has just meant that I’ve had more reason to look around my setup and think of what there was to optimize or change. I figured the first thing I could do would be to update my monster manual from 2014 to 2024 rules. Some time ago, I downloaded a markdown compendium of all the monsters stat blocks formatted in markdown, which made it incredibly easy to just drop into Obsidian (sadly, the repo has since been taken down).

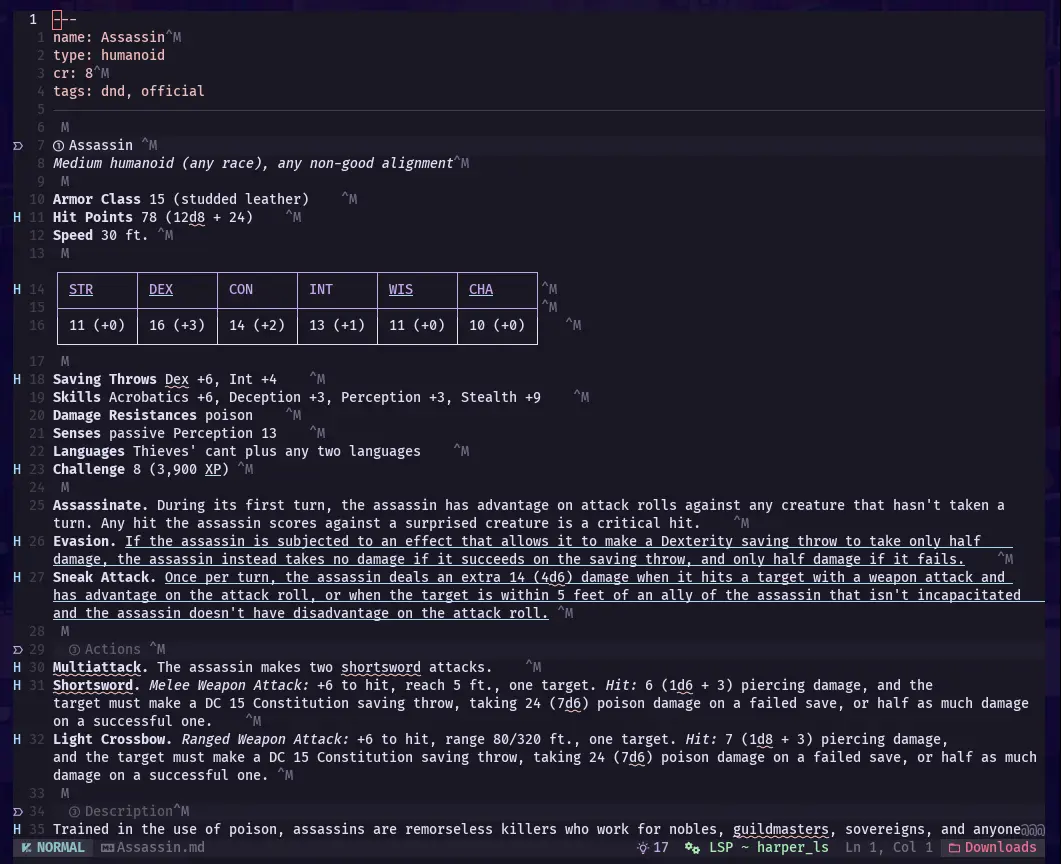

I plopped onto the couch, opened up my laptop, and sshed onto my desktop only to find each of those stat blocks were littered with trailing ^M.

What the hell is this? It doesn’t show up when I open the files in Obsidian, only when I’m viewing them in the terminal. Initially, I thought it was just the file I was working with. I removed those characters manually, made the changes I was looking to make, and hopped into the next one only to find that the ^M was polluting this file, too. Seeing the distraction problem, I started looking into what was causing this and why all the stat blocks were showing up weird in my text editor, but not in viewers.

ASCII Text Encoding

As we all know, computers used to be much bigger. Mainframes would take up entire rooms, if not buildings, and time to those machines would be need to be adequately allocated to everyone looking to use it. To get around this limitation, teletypewriters were partially reworked and integrated into mainframe networks to serve as terminals that interact with the host machines. Protocols like ASCII were then used to communicate instruction sets between the mainframe and the teletype.

That’s a lot of technology and innovations that we just don’t use anymore, at least not nearly to the same extent that we did. But the point that I wanted to draw from it was that protocol in question: ASCII.

ASCII is a standard that allows computers (particularly American English systems) to encode and decode text. Using a seven-bit encoding, each letter (upper and lower case), number, and symbol—or at least a decent number of them—have a respective bit sequence allocated for it.

This is only the characters that we would see printed. In actuality, there are an additional 33 characters that don’t have a symbol. These are the control characters, and they instruct the teletype to do specific things like cancel the incoming signal or ring the bell on the typewriter. Here’s a break down of all those codes:

If you look closely at that table above, you might notice that the 13th line has a special sequence of characters: ^M, which serves as the “Carriage return”. That is exactly what’s occupying the end of my stat blocks. Now, the question comes to why?

Some Things Never Change

This method of text encoding has persisted long since early teletype systems. While modern systems more often rely on Unicode for character encoding, they still use those control codes for reading and printing text.

Windows has a classic text editing tool called Notepad. I’m sure we’ve all used it at least once. As you can see from the screenshot above, it has text at the bottom of the window screen: Windows (CRLF). What does that mean? MS DOS, Microsoft’s operating system before Windows and how they made a name for themselves, used ASCII. When you wanted to end a line of text, you would need to tell the computer to perform a carriage return, \CR, and linefeed, \LF. This would bring the cursor, or where the computer would input text, from the end of the line to the beginning of the next line. Windows still has that encoding at the end of each of their lines, so that the text written in Notepad is still interoperable with older machines of yesteryear.

Linux does it differently.

Linux was built as an imitation of Unix which didn’t use that \CR for handing the end of a line. Instead, it only needed \LF. This is where that problem comes from. The stat blocks that I got were written on a Windows machine and I was opening it on my Linux box. Since Linux doesn’t use the \CR when handling newlines, it just printed them onto the screen as it would other characters.

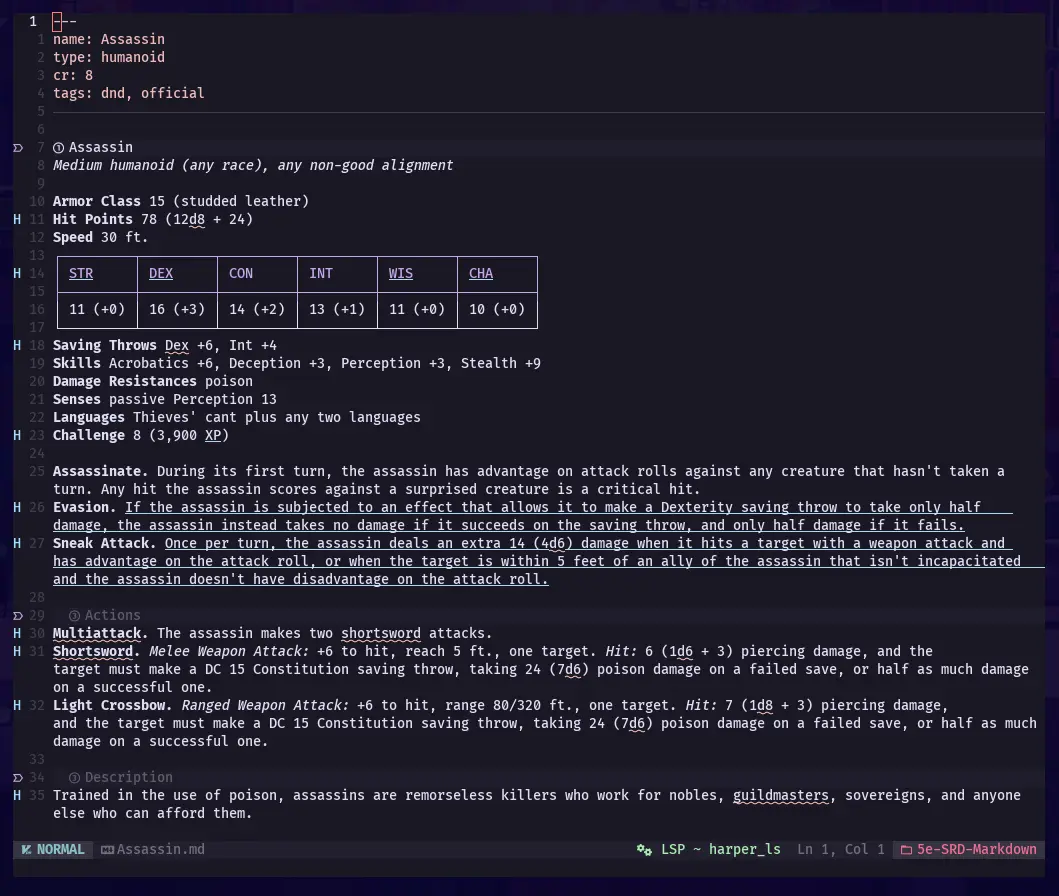

For this reason, there are small utilities like dos2unix or unix2dos that change the line endings to work with your machine. Once I put it through that tool, voilà!

Hallelujah! I ran that tool across all my monsters, and they look perfect!

I wondered to myself why those \CR didn’t show up in Obsidian, but it turns out most tools (particularly those not meant for coding) just sort of accept either of those end of line signals. So long as it has at least one, it follows it.

It’s kind of no wonder prepping for adventures takes me so long. It’s always something that has me going down another rabbit hole.

PIKE MATCHBOX 🫡